Last updated on January 15th, 2025 at 11:52 am

People with serious or terminal illnesses have to make difficult choices. It can be hard to understand all the information they get from their doctors. It can also be an emotional rollercoaster for them and their loved ones. What if there was someone to help them make decisions?

That’s where Kristin Nannetti, MSN, RN, CCRN, CHPN, CNL, comes in. As the Palliative Care Coordinator for VHC Health, her job is to guide patients and their families through all the different areas of care for serious illnesses. She talked with NIH MedlinePlus Magazine about palliative care and how it can give people a better quality of life. She also cleared up some misunderstandings about palliative care.

In your own words, what can palliative care look like?

Palliative medicine is for people with serious and complex illnesses. The goal is to reduce symptoms, improve quality of life, and support the patient and their family so they can cope through their treatment. I like to say palliative medicine is the “human side of medicine.” Our goal is to gentle the journey our patients and their loved ones might face.

We support the physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and existential aspects of their condition. That can include symptom management, complex health care navigation, grief counseling, and advance care planning. We also have “goals of care discussions” where we get to know our patients and their loved ones to help them make informed treatment or care decisions. These discussions take an hour or two per visit, and they usually recur over several weeks, months, or even years. We spend as much time as the patient and their family need to understand their condition, treatment options, and plans. We want to make sure they feel supported through it all.

Why did you decide to go into palliative care? What do you find most rewarding about this work?

When I began a career in health care, I did so to help others. Most of my nursing experience before palliative medicine was in critical care, and my initial career goal was to “save lives.” In part, I saw my role as a nurse to fight off death. But while working in the intensive care unit (ICU), I saw a lot of suffering and futile care (care that is unlikely to make a patient better). I experienced moral distress while working in the ICU and felt burned out. I realized that everyone dies, and sometimes the most compassionate thing we can do as clinicians is to aid a peaceful, natural death.

At that time, I thought palliative care was a sad specialty to work in, but I kept feeling drawn to it. So I shadowed a palliative care nurse and took a special nursing course. Then I took a leap and transferred from critical care into palliative medicine. Soon after, I realized my home in health care is in palliative medicine.

Now I know palliative medicine isn’t actually sad—chronic and terminal illnesses are. What’s sad is the suffering people endure with these illnesses and the shortcomings of the health care system. Palliative medicine helps make those sad things better. That’s what’s most fulfilling about my job.

How is the training for palliative care different from other nursing training? Do you need any special skills for this work?

I’ve taken specialized classes, studied palliative medicine texts, trained with other palliative care specialists, and gone to conferences. In palliative medicine, we focus on all areas. I learned from physicians, nurses, social workers, counselors, nursing aides, and chaplains. I learned about diagnostics for complex and terminal illnesses, symptom management, end-of-life care, and disease prognostication—when physicians try to predict how a disease will progress or how much time a person has left to live. I learned about advance care planning, compassionate communication, ethical and legal standards of care, grief counselling, and case management. Plus, I learned how to support patients and families spiritually when they’re going through a crisis.

Clear, compassionate communication and empathy are important special skills required in palliative medicine. Dealing with serious or complex illnesses can be difficult, and patients often struggle to cope. They may be sad or angry, so I let my patients vent, cry, laugh, whatever they need in that moment. You need to be able to understand where those emotions are coming from. I meet my patients where they are in those moments and help them find the path forward while feeling understood and seen.

How do you determine when palliative care is right for a patient?

Anyone with a serious or complex illness that is impacting their quality of life can discuss palliative care with their providers. It’s helpful if patients seek a palliative care consultation as soon as they are diagnosed with a serious illness, especially if their condition requires symptom management or support. But palliative care isn’t just for managing severe pain or for people who are dying. The timing is fluid—patients can begin palliative care at any time during their treatment journey, even very early on, up to and through end-of-life care. In order to know if palliative care is right for you, ask your primary care provider or specialist.

Hospice is a type of medical, supportive palliative care for people with six months or less to live.

What is it like to talk with people about their palliative care planning and decision-making? How do you help patients make tough decisions?

My role is to help patients and families understand what they can expect with their illness, treatments, symptoms, and prognosis. I think of myself as a steward who helps guide them on their journey through illness. Knowledge can be empowering. Having these conversations with patients and their loved ones can reduce their anxiety and fear.

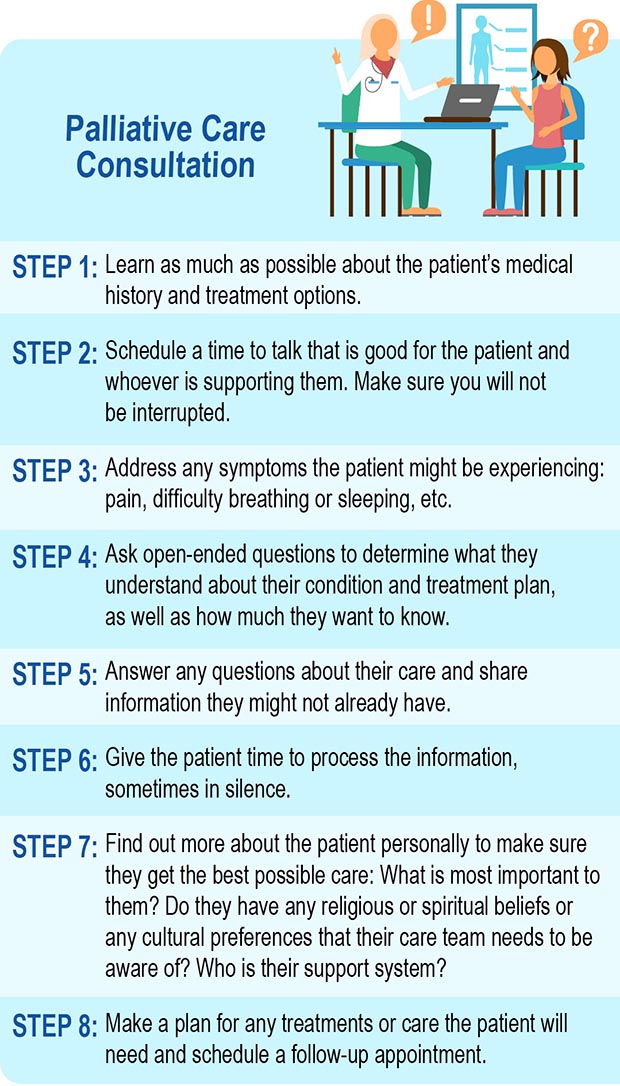

When I start a new consultation, typically the first thing I do is learn as much as I can about the patient’s medical history and treatment options. I make sure that when we have this conversation, it’s comfortable for the patient and whoever is joining us. So we pick a time that’s good for them, find a quiet location, and ensure we won’t be interrupted.

Then I ask them open-ended questions: What do they understand about their condition and treatment plan, and how much do they want to know? Sometimes the discussions can be difficult for the patient and their loved ones to hear, so I give them time and space to digest the information. Often, they need emotional support. This is where my grief counseling skills come in handy. I’ll ask them to tell me about themselves: What’s most important to them? How are they coping with this? Do they have any religious or spiritual beliefs that they lean on during hard times? Do they have any cultural preferences that their care team needs to be aware of? What aspects of their personality should their care team know so that we can give the best possible care? Who is their support system?

By the end of the discussion, we will have a plan for the patient or at least a plan for my follow-up with them. My goal is to ensure they have made an informed decision that reflects their goals and values and that they feel at peace with this decision. I might need to dispel some misconceptions about palliative care and hospice, too. These divisions of medicine are often misunderstood.

For larger image, click here.

What are some common misconceptions around palliative care? How do you address these with patients and their families?

One common misconception is that palliative care is only for people who are dying, but it also maximizes quality of life and reduces suffering. So it’s done together with curative treatments. For example, we could help a person with cancer better tolerate their chemotherapy by managing their symptoms. That can make their treatment more successful and help them live longer and better.

Another misconception is that all palliative care is hospice care. Palliative care is for any stage of a serious illness, but hospice is specifically for patients with a more limited prognosis of six months or less.

A lot of people think that all palliative care clinicians do is offer opioids for pain relief. This is common in palliative care, but it’s not the only way. We also offer non-opioid medications and complementary medicine. These are things like massage therapy, acupuncture, pet therapy, music and art therapy, Reiki, and so on.

Palliative care patients can still see their other physicians, too. We work with other physicians to offer the best possible care, but we do not replace other providers. I correct these misconceptions head on through kind and compassionate education.

How do you manage a situation where the patient’s or family’s desire is different from their health care provider’s recommendation?

This is a common reason palliative care teams are consulted. If the patient or their family are making these decisions based on a misunderstanding or a misconception, maybe they need more information about their condition or their options. Maybe they’re based on religious or cultural reasons. Or maybe they’re concerned about futility of care. If what the patient wants is feasible, then I respect their decision.

If there is still disagreement after these conversations, an ethics consultation may help. Most hospitals have ethicists who speak with both the patient or their surrogate and the medical teams. Their job is to help find a realistic solution for everyone.

What’s an especially memorable experience from your work as a palliative care provider?

I have many wonderful and inspiring memories from my work. My best memories are typically about patients who wanted to cross something off their bucket list before they died and the times I could help them do that.

I’ve participated in a few weddings for patients and for their children. There was a young woman with gastric cancer who wanted to marry her boyfriend—the father of her children—before she died. So the staff on the oncology unit, the chaplains, and I organized a wedding party with cake, balloons, and flowers. She got dressed up, and we got them married in her hospital room. She died later that night, so it was sad, but we were able to provide her and her husband with that final moment of joy. That meant a lot to them.

There are many tragic memories that I have from my career, but I look for good in everything I do and see. I remember a 36-year-old mother with breast cancer whose treatment gave her a few months longer than she would have had otherwise. She was able to spend more time with her family and friends. Witnessing the love she and her husband had was inspiring, and I am grateful that I was able to learn from their example. I believe that even in dire circumstances, we can try to make the situation better for people.

Have you or your loved ones ever received palliative care? If so, what was that experience like for you?

Three of my grandparents died while in hospice care. Each of them had beautiful departures from the physical world. I’m not going to lie—it was challenging. Health insurance doesn’t cover a lot of the day-to-day care that people need at home when they’re sick. So my family and I took turns taking care of them until they passed away. It was a beautiful gift that my grandparents got to die in the comfort of their own homes, without pain or suffering, surrounded by loved ones. And they had peace of mind before they passed away.

And my father-in-law had a palliative care consultation before he died at the end of May. It helped my in-laws and my husband better understand what my father-in-law was going through and what they should expect. Now that we’re grieving his loss, I can see that my husband is better able to cope because he was mentally prepared for what was to come.

What advice would you give to patients and families who are considering palliative care?

I would ask, “Why would you not seek palliative care?” People get sick and die every day with or without palliative care involvement. The difference is that those who have palliative care live better and often longer, and they have that extra layer of support through that difficult journey.